|

.jpg)

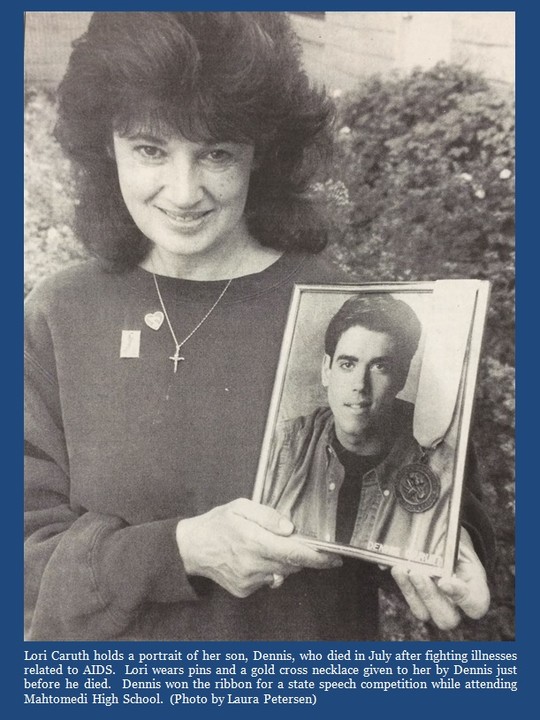

On July 13, former Mahtomedi resident Dennis Caruth died at the age of 27 after living with AIDS-related illnesses for more than 15 months. Dennis and his three sisters and brother were raised by their mother in Mahtomedi. He attended Mahtomedi schools and was very active in plays and musicals in school and at St. Andrew’s Lutheran Church. He was in choir, played the saxophone in the high school band, and was active in the high school debate and speech teams. The day before he died, Dennis asked his mother to write a memorial in his hometown newspaper saying he died of AIDS. It was important to him that his friends, former teachers, classmates, and other area residents know someone close to them had died of the disease. The following is a narrative of Dennis’ life, his struggle with AIDS and his death as told by his mother, Lori Caruth, with the hope other families can learn from his experiences. Lori related Dennis’ story during a series of interviews with Staff Writer Laura Petersen.

by Lori Caruth

I remember his Daddy and I bringing Dennis home from the hospital the day he was born. He had this full head of black hair and weighed nine and a half pounds. He was so cute, bringing him home on that beautiful spring day. He was born on the first day of spring…he always loved those spring flowers. Denny just was always bright, like a bright little star. I remember teaching him his alphabet and he caught on so easily, without having to go over it and over it. He wanted to learn, he was very enthusiastic.

He had this spirit as a child. It brings to mind this play he did in third grade. Denny was this little Indian and it just seemed like he loved being up there on stage, even in third grade, dancing –he had this natural rhythm. He got into doing some other theater stuff. I remember in ninth grade he was doing Jesus Christ Superstar – he was one of the soldiers; after that he was the scarecrow in Wizard of Oz. He just loved it, just loved singing and dancing. He was a natural.

As much as he liked the funky music, he loved Barbara Streisand, Frank Sinatra; he would get the records and bring them home and just sit in his room and play them and sing. And he carried that on. I remember friends would talk about it when he worked at the YMCA in Minneapolis. It would be quiet and all of a sudden Denny would just burst out into a theatrical number and do a little dance in the hall or near the desk and it would make people laugh. People remember that laughter, too. He always had a real deep laugh; I mean you could always tell Denny was in the audience because of his laugh.

Denny was really outgoing like that; he really lived every day, even as a child, to the fullest. And sometimes he would get into mischief, but it wasn’t anything mean or destructive that could hurt someone. He wasn’t that kind of person. His teachers talked about him like that. Mr. Warden, Denny’s speech teacher, wrote in a letter recently that you could hear Denny down the hall and there was this little crowd around him, laughing. He would draw a little crowd and make people laugh.

He was tall, with dark hair, brown eyes, big smile…

One Mother’s Day when he was 16, Denny wrote me a beautiful card on which he drew the most beautiful rainbow – it was reaching for this pot of gold. Inside the card he wrote, “Mom, I want you to pull out this card when times get tough…pull out this card and remember how much I love you…it doesn’t matter what’s going on around.” We were going through some tough times when he made that card. His dad wasn’t there and we struggled. It was real hard. But Denny always wanted so much for me to have happiness. To be 16 years old and have that kind of impact on what he felt about love…Denny was love.

Even right to the end he insisted on having hope and following his dreams. “Nobody has a right to take that hope from you,” he said. After he died, I read that card out loud at a celebration following the memorial. Later, someone said to me, “Denny was a pot of gold.”

After high school, Dennis attended the University of Minnesota, took classes in theater and was active in a fraternity. He worked at several trendy restaurants, including D’Amico Cucina in Minneapolis, where he was assistant manager. He also studied at the Guthrie Theater for a short time.

He had a lot of jobs in restaurants. That’s probably when, you know, he began drinking and stuff – had some hard times there. I would get afraid sometimes, because he would throw a party, like for his sisters, and I would see how he acted. I thought, “could there be a problem here with drinking?” There was also some cocaine going on that I didn’t know about.

He became assistant manager at D’Amico Cucina in Minneapolis. People would request Denny there, they knew they were going to have a good time. One time, somebody asked Denny to serve at their wedding, do the flower arrangements. He would always go that extra mile. But he left after a year. I really don’t know what happened, but I know he was dearly loved there.

He had moved back home and it just wasn’t working out. I was afraid and I didn’t know what the heck was going on with him. I’m grateful to Al-Anon that I started 17 years ago that helped me learn about the disease of alcoholism. I could see he was struggling then, and I let him move back home. But I had to ask him to leave. He would do stuff like driving without insurance, or other things like that that would scare me. I didn’t know if he was using drugs or if he had some other problem. If I saw a sign of cocaine, he would deny it.

He was going to be working at Kincaids, and then he had a kind of bad experience. He went to Michigan thinking it was going to be a good experience, but it wasn’t…he went with someone that he cared for, it was going to be one of those first time things. All I know was that it wasn’t good. It was just before then that he definitely came out, just before he left. We were out for breakfast, and he told me that he was gay. That was probably six years ago. He thought I knew. But I didn’t understand then; it wasn’t talked about then. He would say, “Mom, it’s not anything that you did or Dad did..” – because his father is an alcoholic – it’s that, “Mom, this is how I was born.”

He was in a relationship for a year with a woman that he was in love with, but it didn’t work. He told me, “If I would have married her I would have ruined a marriage. I didn’t want to be like a lot of other men I know that are married and they left the family or they had double lives. I didn’t want to be like that. I could have married this person, but we could have never really been happy.” So he was struggling with being gay. He struggled with that when he was in third or fourth grade, that he didn’t know or couldn’t understand. Even in the lunch room, he would have trouble being in the lunch room with other boys. He couldn’t understand it. As he got older, I didn’t know this, he did some studying on this. After he died, we found an essay that was written on AIDS in a file we were going through with Denny’s things. He would have books on being gay – he studied it.

That brings sadness to me, that I didn’t know or couldn’t understand or couldn’t be there for him in that way. He just said, “Mom, this was the way I was born.” And that must be hard. It’s a lonely life, dealing with the prejudices. When you get into that, you know that other part. One time he said to me, “I’ve been abandoned by men my whole life.” It’s sad.

After that trip to Michigan, he went to Chicago when he was very down. He went with the thought of pursuing his dreams, going to school. He got a really good job as head waiter at Scoo-Z, a famous Italian restaurant. He got accepted at the Centre Theatre an you had to have some talent to be accepted there. He studied there off and on during those four years. He did two, one-act plays there. He was getting ready to help produce his first play before his illness.

During that time, he also was searching for answers… He went to some meetings at Alcoholics Anonymous. There, he met Jules Millan who became a good friend. I went to visit him in Chicago a number of times. We would go to the theater or out to dinner. I don’t know, I guess I felt he had a problem with drinking.

It was the day after St. Patrick’s Day that I got the call. He said, “Mom,” and he was crying. “I hate to do this to you, Mom, but I’m HIV positive and I have full-blown AIDS, and if I don’t get to the hospital right now I’m going to die.”

I was just shaking. I had called the day before and I had just been out there for Valentine’s weekend, but I didn’t know. It felt like something was wrong. Maybe he knew he was HIV positive a short time before and didn’t let us know until he became sick. I couldn’t hear what he said. I kept saying he wasn’t doing anything to me, it’ll be okay, of course. I didn’t know anything about it then…

In March of 1993, Dennis came home to live with his sister Denise and her family in Minneapolis. Six months later, he and his sister Doreen got an apartment together. Through the next 15 months, Dennis became active in various AIDS volunteer efforts and support groups, such as the Minnesota AIDS Project and Pathways in Minneapolis. At the May 1994 AIDS Pledge Walk, two months before he died, Dennis was honored for collecting the largest amount of donations, more than $6,000.

Denny flew home from Chicago at his own risk. He had that AIDS pneumonia, but he survived it. Right away he wanted to know where he was going to be buried and that kind of attitude. But then he got involved with the Minnesota AIDS Project, with fund-raisers and different things to do with families, all kinds of things to do with AIDS. He went and learned about AIDS, took classes at the Red Cross so he could volunteer. He wanted to learn everything he could about his illness. He had us sign up for the AIDS Walk right away in May, while we were still in shock.

But he had a problem with drinking, and I actually confronted him with some of that. I was angry, scared for him. Finally, in the first part of July, he went into treatment at Pride Institute, a (Minneapolis) treatment center for gays and lesbians. He had one year sobriety just before he died. He was very proud of having that sobriety.

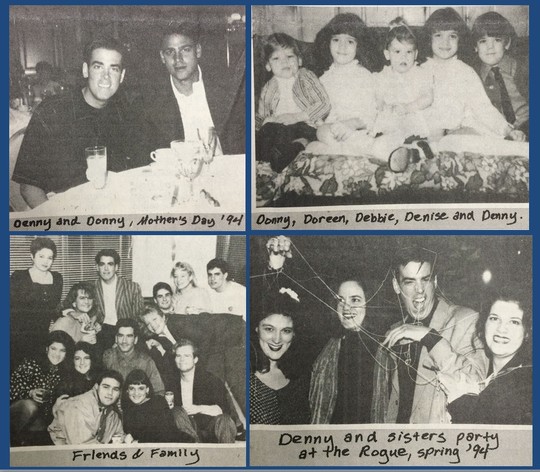

The family, and his friends, were really there for him, though they had to fight through their own fears and the anger. It’s just normal, it’s not anything you can be right on all the time. For my mother, Denny being her first grandson, it was hard. But what made her happy was hearing he was keeping active and never giving up, always keeping that hope. His sisters, Doreen and Denise, they are twins and just a year older than Denny. The three were like triplets, they shared this special bond, and they were there for him always.

Denny’s brother, Donny, was afraid. Here he’s the same age, and here he’s seeing someone his own age, and he’s going to die. Donny probably thought, “This is my brother that’s going to die, and it could be me, I could be getting AIDS. Plus, it’s my brother, someone that I love so much.” That would impact any young person.

It wasn’t all that hunky-dory at all. It was crazy sometimes. I don’t know how we did it, but I would say to them, “You know, there is no right or wrong in this. Hang on to the love, the love is so strong in this family, hang on to that love. There is no right or wrong in whatever we’re doing here.”

Denny never complained about having AIDS. I’m sure he felt sad about it, about having such a short time to live. He didn’t complain about his pain. He never wanted to just accept, like, “I’m going to give up now, because the cancer’s spread to my lungs.” He never would give up, not one day would he give up a chance for another hour, or to plan a new day.

He’d say, “I’m not dying of AIDS, I’m living with AIDS every day of my life.” It took him longer to get going, but he’d say, “I live…” He would even have the nurses laughing. Some days Denny would bring his boom box and he would play Barbra Streisand, or an opera, or some funky music, and he would entertain them all. Here he would be, in intensive care, lying there all hooked up. We didn’t know how Denny came out of it. He could’ve died, and then he came out of it. There were so many ups and downs.

Besides his physician, Dr. Scott Strickland at Park Nicollet Clinic, Denise, Doreen and his mother shared the intensive 24-hour care that Denny needed between his frequent trips to the hospital.

The last three months he was in and out of the hospital. He wanted us to take care of him. It was very good for the family. I remember Donny coming over once when Denny needed to take his shower. Donny pushed Denny in the wheelchair and helped him in the shower and shaving. To help Denny was really very loving and hard for Donny. But to let Denny lean on his brother a little bit was very good. And of course it will leave Donny with so much…

The day before Denny died – we didn’t even know he was dying that day – Denise gave him a ride around Lake Calhoun. He had his oxygen tank, but he could feel that breeze, you know, and there again, that life. He said to Denise, “Run faster, run faster, I want to feel that breeze.”

He had visitors at 7 that night, and (one friend), she came all dressed up like Marilyn Monroe because they knew they were going to hear that laughter. Denny was terribly ill, but they knew they were going to get that one more laugh. It was hard for Denny to talk because the cancer was so think in his throat, but he said, “Now don’t you look cute, get the Polaroid, get the Polaroid.”

And he had a piece of French silk pie and milk at 10:30 that night and I gave him his massage. He said, “Mom, you give the best massages.”

We were planning on going out for a movie and lunch on Thursday. He died on Wednesday. I had no idea that it was going to be that night. I had gone home, left him at 1:30 in the morning; he was there with his sister, Doreen. I had taped that oxygen mask on, and it must have come off around 5 in the morning and that’s when he, he couldn’t breathe. Doreen called the nurse and doctor and they had to use a little bit of morphine, because they said it was going to be a real unpleasant death, from suffocation, and we didn’t want Denny to tough it out or wait too long.

Later, the nurse wanted to increase the morphine, but Denny didn’t want to have it increased. He told Doreen, “No, no, not yet,” because he knew the morphine was going to interfere with his breathing and speed up his death, maybe? He grabbed Denise, who was also in the room, and said, “We have to try one more time Denise, one more time.” And Denise said, “Okay Denny.” But both the sisters knew he would need more morphine.

He never wanted the windows open. He had to have full air conditioning and oxygen. It was hard for him to breathe because of the cancer. Suddenly, he sat up and he had the biggest smile and he said, “You can open the window now, you can open the window now.” And he had obviously seen God, seen the light – he was at peace. But we didn’t know he was dying, because we had never seen anyone die before. I got there at noon and I knew his breathing was awfully different, there was a long time before he’d breathe. He’d breathe, and then there’d be this long pause. His lips were white and his nails were white, and that was a sign, but we didn’t know he was dying. I saw the fluid gurgling here (in his throat) because he had built up a lot of fluid in the last weeks.

The nurse was coming at 3 p.m. She had kind of looked at him and she could tell that, she didn’t want to say it bluntly, but she could tell it was going to be hours. His blood pressure had dropped, it was…that’s what the white lips were about, and…his fingers…were so white…it’s so hard for me to talk about this…

I realize now that when I was there from noon until he died at 4:41, that Denny was just his dying – just like when Jesus died on the cross, you see, and he went through those different things. It was just his body reacting to death. I really believe in that, because it was supposed to be so unpleasant a death.

The moment I believe he really died, and found peace, was when he sat up and asked us to open the window. I can just see him doing that, because he was just so full of life. It was his spirit, whatever he must have seen, I would think Jesus or the other side. That was so beautiful. Denny’s just so alive in all of us. It was such a celebration – again, not a mourning, a celebration, and that’s how he wants to be remembered and that’s how he is remembered.

Half of Denny’s ashes were buried at the cemetery Saturday morning, and we were going to sprinkle the rest down on Nicollet Island. That was Denny’s wish. We all met at Denise’s that Sunday. I remember taking the box containing his ashes off the table, and I put some flowers on it. It was so heavy. I never realized that half the ashes would be so heavy. Later, I sat in the car holding this close to my heart, and I got in touch with that feeling. I was crying because I was feeling such sadness, because I was going to have to let go of this other part of him. It felt like he was a little baby, like when his dad and I brought him home from the hospital, it felt like it was the same weight, just this little bundle…and here I’m going to be taking him to this other place now.

I walked out of Denise’s house, down the street, crying and talking to Denny with this box, telling him how I have to release this. I was so sad, grieving, and not wanting to accept that his body was gone, and he’s in heaven. Then I turned around and my grandson, Marcus, was standing on the steps there, with his little blond head, waving to Grandma. I looked at him and I waved, and all of a sudden he just darted down the street in his bare feet and diaper – he’s going to be two – all the way down the block and into my arms. Here I had that box, and here I had the real thing. I know that was Denny’s spirit that is always so alive every day. I know it was Denny knowing that I was feeling so sad, and he said, “Here, I’m going to give you the real thing.”

So these are things I feel every day, even though I feel like I can’t get through a day, I know what comes out is his spirit. It can be anything I do, it can be someone I meet, a stranger I might meet, and something I say might help that person. They were Denny’s thoughts and my thoughts too, but they’ve come together. I don’t even know where they come from – well, I know where they come from, they come from God, that spirit of God that I found.

|